By now, those who pay attention to poetry and in particular the poetries of witness and activist poetries, know well that they follow from a long tradition. Yet others, especially cultural and political conservatives, argue “protest” poetry or “political” poetry both do not constitute “Literature,” and that such poetry cannot help but be time-bound little more than contemporaneous commentary. I have been told that some of my poetry is “journalistic,” and that I am caught in a “fashionable” trend stemming from the mid-1950s protest poetry and that it has no literary roots beyond, possibly, the Beats. Such arguments simply are nonsense.

Carolyn Forché’s volumes Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English 1500–2001 and Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness demonstrate, with excellent examples, a long history of social and political engagement in English poetry. In fact, one might argue just the opposite of the (usually disguised political) claims that the tradition began in the middle of the 20th C—that solipsistic confessional poetry that is more autobiography than engaged in the world emerges from that time, in counter-balance to a history of poetry engaged in the outside world.

For this post, I provide two examples of poets from the first half of the 20th Century who engaged in the world.

The first, two poems come from the well-known poet William Butler Yeats: Easter, 1916, written in response to a political protest forcefully broken up by the British, who executed, some would say massacred, 16 of the protesters. The poem, written in September 1916 and published in 1928, ends with a powerful commentary on the protest, the execution-martyrdom that resulted, and, prophetically, the continuation of the Irish struggle: “A terrible beauty is born.”

Easter, 1916

William Butler Yeats

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman’s days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our wingèd horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven’s part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse—

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Yeats’ poem, “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” comments powerfully and bitterly on violence, war, oppression, and the loss of our own humanity in modern times. The poem, in six parts, has a history of difficult critical reception—critics had a hard time reconciling it with others of Yeats’ works. However, since the later part of the 20th Century, his poem has had a more thoughtful reading by the critics, possibly giving weight to saying he was “ahead of his time.”

Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen

William Butler Yeats

I.

Many ingenious lovely things are gone

That seemed sheer miracle to the multitude,

protected from the circle of the moon

That pitches common things about. There stood

Amid the ornamental bronze and stone

An ancient image made of olive wood —

And gone are Phidias’ famous ivories

And all the golden grasshoppers and bees.

We too had many pretty toys when young:

A law indifferent to blame or praise,

To bribe or threat; habits that made old wrong

Melt down, as it were wax in the sun’s rays;

Public opinion ripening for so long

We thought it would outlive all future days.

O what fine thought we had because we thought

That the worst rogues and rascals had died out.

All teeth were drawn, all ancient tricks unlearned,

And a great army but a showy thing;

What matter that no cannon had been turned

Into a ploughshare? Parliament and king

Thought that unless a little powder burned

The trumpeters might burst with trumpeting

And yet it lack all glory; and perchance

The guardsmen’s drowsy chargers would not prance.

Now days are dragon-ridden, the nightmare

Rides upon sleep: a drunken soldiery

Can leave the mother, murdered at her door,

To crawl in her own blood, and go scot-free;

The night can sweat with terror as before

We pieced our thoughts into philosophy,

And planned to bring the world under a rule,

Who are but weasels fighting in a hole.

He who can read the signs nor sink unmanned

Into the half-deceit of some intoxicant

From shallow wits; who knows no work can stand,

Whether health, wealth or peace of mind were spent

On master-work of intellect or hand,

No honour leave its mighty monument,

Has but one comfort left: all triumph would

But break upon his ghostly solitude.

But is there any comfort to be found?

Man is in love and loves what vanishes,

What more is there to say? That country round

None dared admit, if Such a thought were his,

Incendiary or bigot could be found

To burn that stump on the Acropolis,

Or break in bits the famous ivories

Or traffic in the grasshoppers or bees.

II.

When Loie Fuller’s Chinese dancers enwound

A shining web, a floating ribbon of cloth,

It seemed that a dragon of air

Had fallen among dancers, had whirled them round

Or hurried them off on its own furious path;

So the platonic Year

Whirls out new right and wrong,

Whirls in the old instead;

All men are dancers and their tread

Goes to the barbarous clangour of a gong.

III

Some moralist or mythological poet

Compares the solitary soul to a swan;

I am satisfied with that,

Satisfied if a troubled mirror show it,

Before that brief gleam of its life be gone,

An image of its state;

The wings half spread for flight,

The breast thrust out in pride

Whether to play, or to ride

Those winds that clamour of approaching night.

A man in his own secret meditation

Is lost amid the labyrinth that he has made

In art or politics;

Some Platonist affirms that in the station

Where we should cast off body and trade

The ancient habit sticks,

And that if our works could

But vanish with our breath

That were a lucky death,

For triumph can but mar our solitude.

The swan has leaped into the desolate heaven:

That image can bring wildness, bring a rage

To end all things, to end

What my laborious life imagined, even

The half-imagined, the half-written page;

O but we dreamed to mend

Whatever mischief seemed

To afflict mankind, but now

That winds of winter blow

Learn that we were crack-pated when we dreamed.

IV.

We, who seven years ago

Talked of honour and of truth,

Shriek with pleasure if we show

The weasel’s twist, the weasel’s tooth.

V.

Come let us mock at the great

That had such burdens on the mind

And toiled so hard and late

To leave some monument behind,

Nor thought of the levelling wind.

Come let us mock at the wise;

With all those calendars whereon

They fixed old aching eyes,

They never saw how seasons run,

And now but gape at the sun.

Come let us mock at the good

That fancied goodness might be gay,

And sick of solitude

Might proclaim a holiday:

Wind shrieked — and where are they?

Mock mockers after that

That would not lift a hand maybe

To help good, wise or great

To bar that foul storm out, for we

Traffic in mockery.

VI.

Violence upon the roads: violence of horses;

Some few have handsome riders, are garlanded

On delicate sensitive ear or tossing mane,

But wearied running round and round in their courses

All break and vanish, and evil gathers head:

Herodias’ daughters have returned again,

A sudden blast of dusty wind and after

Thunder of feet, tumult of images,

Their purpose in the labyrinth of the wind;

And should some crazy hand dare touch a daughter

All turn with amorous cries, or angry cries,

According to the wind, for all are blind.

But now wind drops, dust settles; thereupon

There lurches past, his great eyes without thought

Under the shadow of stupid straw-pale locks,

That insolent fiend Robert Artisson

To whom the love-lorn Lady Kyteler brought

Bronzed peacock feathers, red combs of her cocks.

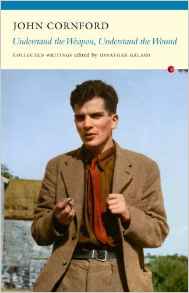

For the second example, I move to a lesser-known writer. John Cornford, the great-grandson of Charles Darwin, died during the Spanish Civil War under “uncertain circumstances at Lopera, near Córdoba in 1936.” We have no idea how much he might have contributed to poetry, had he survived. However, his poems written during the Spanish Civil War did survive, and were published posthumously. Born in 1915 in Cambridge, England, he was a committed communist. “Though his life was tragically brief, he documented his experiences of the conflict through poetry, letters to family and his lover, and political and critical prose which spoke out against the fascist regime and its ideologies.”

Sandra Mendez, a niece of John Cornford who also holds the copyright to his work, created a song from his poem “To Margot Heinemann.” The YouTube below is her performing that song.

These are just two of many examples that could be drawn from the long history of English letters. Engaged poetry, poetry of witness, activist poetry, political poetry—all comprise an important aspect, perhaps the most important aspect, of what we call “Poetry.”

Select Resources and Links

Burt, Stephen. The Weasel’s Tooth: On W. B. Yeats. The Nation.

Dickel, Michael. Curator / Editor. Poet Activists: Poets Speak Out. The Woven Tale Press.

Rumens, Carol. Poem of the Week: Poem by John Cornford. The Guardian.

On this blog

poetics on Robert Duncan’s birthday

The Hero’s Journey and the Void Within: Poetics for Change

Joy Harjo—Fear Poem

Michael Rothenberg and Mitko Gogov

Since this was originally posted

The BeZine | May 2017

It’s impossible to separate activism from current poetry, especially since the rise of the beat movements and civil rights movements. The use of poetry as protest has always had strong roots, but when folk music, with it’s strong marriage to poetry, gained currency as popular music, it became a political force in this country.

I personally had the honor of writing, performing and protesting in Austin with the late Susan Bright who founded Plain View Press, and Raul Salinas who founded the Resistencia project. Raul forged his craft in prison and when he returned he was a force for change and escape from the gangs in Austin’s poverty stricken east side. Susan worked with oppressed women’s rights movements around the world.

Both inspired hundreds of young poets, many who became political activists as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are sites publishing activists poetry that have wonderful poems highlighting the issues of today. Many of the poets are not of the status of the above but they are good. Have a look at “I am not a silent poet” and Writers Against Predujuduce for example.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m aware of them, thank you, Carolyn. It’s useful for others to know them, as well.

I am not a silent poet https://iamnotasilentpoet.wordpress.com/

Writers Against Prejudice https://writersagainstprejudice.wordpress.com/

Big Bridge http://bigbridge.org/BB19/index.html

Are just three. As well as http://100TPC.org

LikeLike

Thought you might know them but just wanted to add to the debate, it’s great that you’ve added the links and Jamie will feature them. More opportunities the better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bravo, Michael. Would like to post this on “The Poet by Day” on Monday. Okay with you?

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would be great, Jamie! Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person